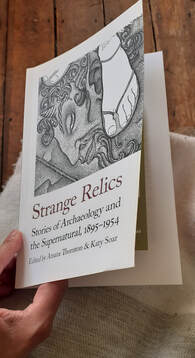

This month's big news is that a project two years and a few lockdowns in the making has finally come to fruition! Strange Relics, an anthology of classic supernatural stories with an archaeological twist that I have co-edited with Dr Katy Soar, has been published by Handheld Press.

|

By Amara Thornton This month's big news is that a project two years and a few lockdowns in the making has finally come to fruition! Strange Relics, an anthology of classic supernatural stories with an archaeological twist that I have co-edited with Dr Katy Soar, has been published by Handheld Press. One of the inspirations behind the development of the project was my post from October 2019, #ExcavationGothic. It started an avalanche of sorts - brought me a great collaborator, Dr Katy Soar, and led me down the rabbit hole of digitised copies of Weird Tales. I hope you enjoy it as much as I have in working with Katy to bring it together! Strange Relics is available to order through Handheld Press: www.handheldpress.co.uk/shop/fantasy-and-science-fiction/strange-relics-stories-of-archaeology-and-the-supernatural/

By Amara Thornton

I came across the magazine Egypt and the Sudan while finishing up Archaeologists in Print. But it wasn't till after the book was published that I had the chance to look at a full run of the magazine, which is held at the Egypt Exploration Society. You can find my post "A Magazine for the Season" on the Egypt Exploration Society's blog here. By Amara Thornton

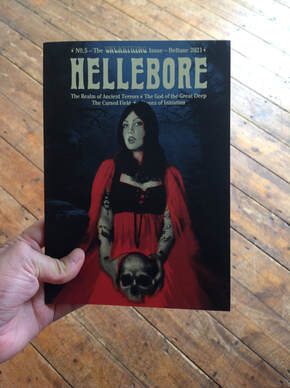

I'm delighted to have an article published in Issue 5 of Hellebore, a zine of essays and art on various gothic and folk-horror related topics, under a general theme. Issue 5's theme is "The Unearthing"; my article "The Stones of Initiation" explores how the history of archaeology in the Caribbean connects to the Caribbean folk-practice Obeah. By Amara Thornton

In the past month I've finally been able to return to the British Library. I'd had a number of things I'd been wanting to see, including two issues of the Victoria Quarterly, a Jamaica-based literary journal published in the 1890s. Having first learned about the journal in the course of researching last month's post "Colonial Archaeology in the Caribbean", I was hoping to see the issue in which Lady Edith Blake published the article on her excavations on a kitchen midden at Norbrook (Northbrook), near Kingston. But it was not to be – the British Library's two issues were not the ones in which Blake's article appeared. But all was not lost – in flipping through one issue, from July 1892, I came across Mrs Spencer Heaven's story "My Family Mummy". The plot summary is as follows: a party of young cousins are in the ancestral family home over the Christmas holidays. The one 'grown up' around – Aunt Bessie – leaves them to their own devices and only communicates with them through (affectionate) notes. As boredom descends upon the young folks, one of them remarks that the family has a mummy stored away in the attic, a 'relic' of a long-dead ancestor's travels in Egypt. All the others are determined to see the mummy and so they make a pilgrimage to the attic. One of the girls, Maud, sees the mummy for what it is – a human being – and tells the others that respect should be paid to it. Eventually she convinces everyone that the mummy, nicknamed "Miss Pharaoh" should be reburied. After some discussion, during which it is determined that no suitable ground could be found for the reburial, Maud decides that cremation would be best. A day is chosen, the fire built and "Miss Pharaoh" burned. The cousins abandon the fire to the care of servants and go to town, but it transpires that eventually the servants are arrested for murder; the police have found a burning corpse in thier charge. The young folks are both horrified and convinced that "Miss Pharaoh" is seeking revenge. However, the story ends tidily with them rescuing the servants from probable hanging by explaining the situation in court. The story is presented as being an anonymised re-telling of events that actually happened – whether or not that is true I'm not sure! But it's certainly fictionalised, if not fiction. Having literally just listened to an excellent panel on ancient Egyptian human remains ("Your Mummies Their Ancestors") this 19th century story reflects a discussion about how 'mummies' are viewed, displayed and interpreted that is still continuing today. [Originally from Devon, Selina Frances Smyly married De Bonniot Spencer Heaven of "The Rambles" and "Whitfield Hall" Jamaica in 1864. She lived in Jamaica for many years before returning to Britain, where she died in 1911. She was a musician and botanist as well as a writer.] References/Further Reading Colonies and India. 1893 [News]. [British Newspaper Archive]. 4 Feb: 11. Exeter and Plymouth Gazette. 1864. Abbotsham. Wedding Festivities. [British Newspaper Archive]. 11 Nov: 6. Heaven, Mrs Spencer (Selina). 1892. My Family Mummy. Victoria Quarterly 4 (2): 16-26. Stienne, Angela (Ed). Mummy Stories[Blog] Western Daily Press, 1911. Deaths. [British Newspaper Archive]. 26 June: 10 Hartland and West Country Chronicle. 1911. [News] [British Newspaper Archive]. 15 June: 9. By Amara Thornton

I put out a request on Twitter this morning with a Halloween-y twist. Use the hashtag #excavationgothic to add to the bibliography (below) of works featuring excavation (or antiquities) in a gothic setting! Thank you to all the stellar folks who have already responded! The results, so far, are as follows (chronological, by date of publication). 2nd C: Pliny the Younger, "To Sura" 1820s 1827: Jane (Webb) Loudon, The Mummy! Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century 1860s 1862: Anon, "The Mummy's Soul" 1867: Louisa May Alcott, "Lost in a Pyramid" 1868: Jane Austin, "After Three Thousand Years" 1880s 1882: Theophile Gautier, "The Mummy's Foot" 1885: Thomas Hardy, "A Tryst in an Ancient Earthwork" 1887: Mary Elizabeth Braddon "From a Doctor's Diary" 1889: Eva Henry, "Curse of Vasartas" 1890s 1890: Thomas Hardy, "Barbara at the House of Grebe" 1892: Arthur Conan Doyle, "Lot No 249" 1892: Grant Allen, "Pallinghurst Barrow" 1895: Arthur Machen, "The Novel of the Black Seal" 1898: Herbert Crotzer, "The Block of Bronze" 1898: Arthur Conan Doyle, "Burger's Secret" 1898: E & H Heron (Hesketh Pritchard and Kate Pritchard), "The Story of Baelbrow" 1900s 1904: Charlotte Bryson Taylor, "In the Dwellings of the Wilderness" 1904: Montague Rhodes James, "Oh Whistle and I'll Come to You, My Lad" 1908: Algernon Blackwood, "The Nemesis of Fire" 1910s 1910: Arthur Conan Doyle, "Through the Veil"; "The Terror of Blue John Gap" 1911: Gilbert Keith Chesterton, "The Ballad of the White Horse" 1913: Anon, "The Aldbrickham Skeleton" 1919: Francis Brett Young, "Song of the Dark Ages" 1920s 1921: Algernon Blackwood, "The Tarn of Sacrifice" 1921: Howard Phillips Lovecraft, "The Nameless City" 1924: Howard Phillips Lovecraft, "Imprisoned with the Pharaohs" 1924: Howard Phillips Lovecraft, "Under the Pyramids" 1924/5: Gilbert Keith Chesterton, "The Curse of the Golden Cross" 1925: Howard Christopher Bailey, "The Long Barrow" 1925: Montague Rhodes James, "A Warning to the Curious" 1928: Edward Frederic Benson "The Temple" 1929: Eleanor Scott, "The Cure" 1929: Eleanor Scott, "Celui-la" 1930s 1931: Howard Phillips Lovecraft, "At the Mountains of Madness" 1933: Robert E. Howard, The Cairn on the Headland" 1934: Elliott O'Donnell, "The Mummy Worshippers" 1934/35: Howard Phillips Lovecraft, "Shadow Out of Time" 1935: Clark Ashton Smith, "The Last Hieroglyph" 1935: Joseph O'Neill, "Land Under England" 1938: Thomas P. Kelley, "I Found Cleopatra" 1938: Edgar Hoffman Price, "The Woman in the Case" 1938: Dorothy Kathleen Broster, "The Pavement" 1940s 1945: Alfred Leslie Rowse, "The Stone that Liked Company" 1949: Nigel Kneale, "Minuke" 1950s 1951: Sarban (John William Wall), "Ringstones" 1951: Sarban (John William Wall), "Capra" 1951: Margery Lawrence, The Rent in the Veil 1952: Rose Macaulay, "Whitewash" 1970s 1971: Ramsey Campbell, "The End of a Summer's Day" 1971: Daphne Du Maurier, "Not After Midnight" 1975: Rosemary Timperley, "The Bandaged Man" 1980s 1989: Anne Rice, The Mummy, or Ramses the Damned 1990s 1996: Joyce Carol Oates, "The Temple" 1996: Neil Gaiman, Neverwhere 2010s 2010: Rosalie M. Parker, "The Old Knowledge" 2013: Adam Roberts, "Tollund" 2013: Roger Luckhurst, "The Thing of Wrath" 2014: Robert Sharp, "The Good Shabti" 2014: Lesley Glaister, Little Egypt By Amara Thornton This month's blog is on Ure Routes, as last week we installed a new exhibition at the Ure Museum, "Allen Seaby's Archaeology for Children". The genesis of the display goes back to my first few months at Reading. I met Laura Carnelos, who was then cataloguing collections in the Typography Department. She drew my attention to some material she was working on that was relevant to archaeological publishing. One of them is the archive of artist Allen Seaby.* Seaby was a Professor of Fine Art at Reading in the early 20th Century, but he also wrote books on archaeology for children. Laura had in the course of cataloguing come across an unpublished manuscript, "Leon of Massalia", a story set in ancient Greece. Of course, this intrigued me because of the books for children I wrote about in Archaeologists in Print. It led me to look more into Seaby's works, and the ways in which he presented archaeology and archaeological discoveries for younger readers. A few months later, we were installing the exhibition! It took on a new form at rather the last minute, with a unexpected and very generous loan of lots of relevant sketches and preliminary drawings from Allen Seaby's grandson, the artist Robert Gillmor, to whom we are extremely grateful. With installation imminent, Ure Museum curator Professor Amy Smith and I sat down and talked through Seaby's life, and the materials we had gathered on loan from Robert Gillmor, the Typography Department and the Children's Collection (part of Special Collections). The concept ended up falling rather naturally into chronological phases when mapped against Seaby's life; these became "Chapters", mimicking a book, as I drafted the handlist. You can read more about Seaby at "Allen Seaby and Archaeology" and by visiting the exhibition at the Ure Museum, on until 21 February! Use the hashtag #SeabysArchaeology to tell us what you think of the display.

*The other is the Isotype collection. By Amara Thornton

This month's post is over on "Beckett, Books and Biscuits", the blog for Special Collections at the University of Reading. I've been spending some time diving into a wonderful archive held there, the papers of Adam & Charles Black, publishers. A. & C. Black (for short) published both fiction and non-fiction, but I'm particularly interested in their non-fiction publishing efforts. Among this group can be counted a number of popular archaeology books written by Rev. James Baikie, and illustrated by his wife Constance Newman (Turner-Smith) Baikie. I've written about one of Baikie's books – Wonder Tales of the Ancient World – here already. But this new research has helped contextualise both Baikies' work significantly. Although he wasn't an archaeologist, as I noted in Archaeologists in Print James Baikie was a prolific author of popular archaeology books – a pre-WW2 Leonard Cottrell – or, to use a more contemporary example, Tony Robinson. Constance Baikie, an unsung illustrator today, produced in my opinion brilliant work complementing and visually enhancing her husband's text. This took not just skill, but genius. I'm happy to say that A. & C. Black recognised her impact, crediting and paying her accordingly. There's a lot more to the A. & C. Black collection than just information on James and Constance Baikie. It's full of authors and illustrators whose work is today almost totally unknown, but there are also more famous names, as you'll see. The Indexes to the "Letters Out" books – my main source for the post – are fascinating. I found myself wondering about the lives of those listed. Hopefully, more of them will be revealed. You can read "Recovering Publishing Histories: The Adam and Charles Black Letterbooks" here. By Amara Thornton Do you know about Tausret? She was a queen in ancient Egypt. 19th dynasty to be precise. Until a few months ago I'd never heard of her, but now I know more – thanks to a rather intriguing book: Janet Buttles' The Queens of Egypt.* Earlier this month I was prepping for Suffrage Standup, an event I took part in at LSE Library, and researching Margaret Murray's participation in a suffrage Costume Pageant and Dinner. As Margaret Murray probably attended the dinner dressed as Tausret, I was hoping to find out a bit more about this ancient royal. And so I did, thanks to Janet Buttles. Buttles was an American writer who was associated with American industrialist and archaeology funder/excavator Theodore Davis. Her biographical details are online courtesy of the Emma B. Andrews Diary project– a fascinating digital diary and data resource revealing early 20th century Egypt through the eyes of Emma Andrews, an educated American tourist and collector. Andrews was Buttles' aunt as well as Theodore Davis's collaborator and mistress for many years. Queens was Buttles's attempt to do something innovative in the field of Egyptology. She pulled together in one volume all the details that were known at that time about ancient Egyptian royal women. And in doing so she articulated one of the main (and continuing) problems with making historical women more visible – missing or inaccessible historical records. In her Preface she stated: So many of the royal women who shared the throne of the Pharaohs have left no traces on the land of their inheritance, that this attempt to tell their story results at best in only a brief outline of the prominent figures…" Gaston Maspero, a former head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, wrote an introduction to Queens. He mentions the value of Buttles's personal experience with the archaeology of Egypt in making her sympathetic to her subjects. The book is organised chronologically, from the 1st to 26th dynasty (omitting the Ptolomaic period, which included the reign of Cleopatra VII). Despite the sketchy details available, Buttles's description of Twosret's life is intriguingly dramatic: This heiress of the kingdom claimed the crown of the Pharaohs as her birthright… a dominating princess who claims the right to active government; an elder brother who wrenches the sceptre from her grasp; his speedy exit by fair means or foul; the queen's restoration, and a joint rule with a second brother lasting only a few years, when they are both superseded by a fourth claimant." Archibald Constable & Co published Queens in 1908, at a period when suffrage campaigns were beginning to turn towards greater militancy. And it was reviewed in a suffrage periodical, Women's Franchise. The review opens with the observation that Buttles's work was "A valuable addition to the knowledge of the position of women in antiquity".

Now I know about it, I'll be dipping into Buttles's book to discover more ancient historical women in influential roles. You should too! References/Further Reading Buttles, J. 1908. The Queens of Egypt. London: A. Constable & Co. Cana, F. B. 1908. Where Civilization Began. Women's Franchise [British Newspaper Archive] 13 Aug: 80. *There are many alternative spellings for Tausret's name. Between 2004 and 2016 the University of Arizona ran an excavation project at Tausret's temple in Thebes. More information and up-to-date analysis can be found here and here. By Amara Thornton

When my grandparents retired, they started taking classes for fun. One of these classes was in memoir writing, so when I was growing up we'd receive a letter every so often with a short memoir-essay enclosed. I read them at the time, but didn't consider them anything more than entertaining anecdotes. But now, with my historian's hat on, I see that they are really valuable insights into 20th century experience, and I thank my lucky stars that my grandparents made the effort to write those memories down. A few years ago I found a binder full of copies of these short memoirs, which my grandmother had kept along with other family papers. I've now informally digitised it all, so that I can take these little snippets of family history with me wherever I go. One of my favourites was written by my grandfather, in which he remembered (among other things) how much he loved reading "penny dreadfuls" as a child, and how they instilled in him a love of history. My great-grandmother disapproved of such books and eventually threw them away. In doing so, my grandfather reasoned, she had gotten rid of what could have been quite a valuable collection. I'd like to think that I inherited something of my grandfather's appreciation for pulp. I managed to incorporate a bit of discussion of archaeological pulp (via Margery Lawrence's contributions to Hutchinson's Mystery Stories magazine) in Archaeologists in Print. But I'm always on the lookout, so I was very pleased when I spotted at a recent pulp-focused bookfair in London Pauline Stewart's* Delia's Quest for the Golden Keys, "A Thrilling Desert Adventure Story", on a table. It is No 549 of "The Schoolgirls' Own Library", priced at 4d (it cost me £3). Its bright yellow paper cover features a girl dressed in ancient Egyptian garments with a tall headpiece standing on some sort of platform being pushed towards a temple (half submerged in water, so I'm assuming Philae) by a chap looking remarkably like a swimming 1930s filmstar. It's dated 6 August 1936. Happily, "The Schoolgirls Own Library" is a series I've come across before, while I was writing Archaeologists in Print and looking for information on pulp serials. There are a number of websites out there for collectors and readers of such books, and Friardale is one of them. It's excellent, and has loads of resources available in pdf form. There is also a list of titles in "The Schoolgirls Own Library" (and affiliated publications), so you can get a sense of the adventures those schoolgirls get up to. A proportion of them have vague connections to places that were for most British readers 'exotic'. So, alongside Delia and her Golden Keys, we have No 688, Hilda Richards'** "Babs & Co in Egypt" (how I wish that one were available!) which has on its bright yellow cover a gaggle of teenage schoolgirls pointing a flashlight at a rather shocked-looking mummy standing at the entrance to an ancient Egyptian tomb. You can find a list of "Schoolgirls Own Library" titles here. I haven't yet gotten more than a few pages into Delia's Quest, but I'm intrigued to see whether any archaeologist characters crop up in it. Based on the cover, I'm hoping so. At the very least, it'll be an insight into how Egypt (and British tourists' relationship to Egypt) is portrayed in this kind of work. Maybe that portrayal will surprise me. But I'm not getting my hopes up too much. * a pseudonym – the author was Reginald Kirkham. See Dennis Bird's list of SGOL authors. ** a pseudonym – the author was John Wheway as per Dennis Bird's list. By Amara Thornton

My first book, Archaeologists in Print: Publishing for the People, has been published today by UCL Press. It's available to read for free, open access, via UCL Press's website. You can also purchase a paperback or hardback copy, should you want one, from the same link. The book is the culmination of a research project on the history of popular publishing in archaeology, which was funded through a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship, which I held from 2013 to 2016. Focusing on the late 19th and early-mid 20th centuries, I explore the varied ways in which British archaeologists (men and women, many working primarily overseas) wrote about archaeology for a non-scholarly audience. Along the way, Archaeologists in Print reveals the personal histories of many archaeologist-authors during this time period, drawing on extensive research in archives, as well as lots and lots of newspapers. It connects this archaeological publishing history to wider cultural, social, political and economic contexts, including travel and tourism, education, gender, professional development, communication technologies and imperialism. I've encountered many fascinating texts and authors through researching and writing this book. You can find more discussion of some of them by going through the entries on this blog, which I began when I started the postdoc in 2013. Happy reading! |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed