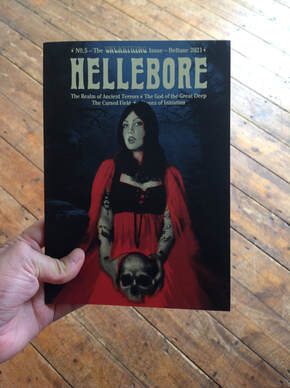

I'm delighted to have an article published in Issue 5 of Hellebore, a zine of essays and art on various gothic and folk-horror related topics, under a general theme. Issue 5's theme is "The Unearthing"; my article "The Stones of Initiation" explores how the history of archaeology in the Caribbean connects to the Caribbean folk-practice Obeah.

|

By Amara Thornton

I'm delighted to have an article published in Issue 5 of Hellebore, a zine of essays and art on various gothic and folk-horror related topics, under a general theme. Issue 5's theme is "The Unearthing"; my article "The Stones of Initiation" explores how the history of archaeology in the Caribbean connects to the Caribbean folk-practice Obeah. By Amara Thornton

I spent quite a bit of 2020 researching the history of archaeology in the Caribbean. Last month I launched a website that included digital interactive on archaeological collections histories linking Britain and Barbados. Among the locations highlighted on the map of Britain in "Mapping Collections Histories" is South Kensington, where in 1886 the Colonial and Indian Exhibition took place. I've been interested in temporary exhibitions of archaeology for years now; my initial efforts to trace the small annual temporary displays of material excavated by British archaeologists in Egypt, Sudan, Palestine and Iraq in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was published in 2015. There were displays of archaeological material in World's Fairs, too - I've blogged about the displays of ancient Egyptian artefacts at the 1904 World's Fair in "I'll Meet You in St Louis". The Colonial and Indian Exhibition in 1886 included displays of 'archaeological' material (by which I mean artefacts that were at the time considered to be material culture from the ancient Indigenous peoples of the islands, usually called "Carib relics") from across the Caribbean, including Barbados, St Kitts, British Guiana (Guyana), Dominica, St Vincent, Jamaica, and Trinidad. But as I've recently found out, it wasn't the first time collections of artefacts from the Caribbean were brought together. In 1879, a series of local exhibitions were instigated in British Guiana, in part to strengthen ties and encourage friendly competition between colonies in the Caribbean. A description of the 1882 exhibition was published in Timehri, the journal of the colony's Agricultural and Commercial Society. The displays were grouped into two broad categories – sugar, and everything else. The second (miscellaneous) group included manufactured products, and antiquities. The exhibition featured two collections, one of artefacts from St Vincent belonging to Edward Leycester Atkinson, and the other from St Lucia, belonging to a Mr Rousselet. The following exhibition did not take place until November 1885, on a slightly grander scale. The British Guiana and West Indian Exhibition featured displays from Guiana and beyond. It was hoped that other islands would contribute, but the Timehri report on the exhibition noted that calls for displays for the Colonial and Indian exhibition had diverted much desired material to London. Among the islands that did respond were St Vincent, Tobago, Trinidad and Dominica. Again among the Miscellaneous group of the exhibition were collections of artefacts for display. Dr Henry A. Alford Nicholls, an English physician resident in Dominica who had an interest in zoology and horticulture, sent a collection of antiquities from that island (for which he won a prize). These had been previously displayed at an exhibition in the Courthouse, in Roseau, Dominica's capital, held to fundraise to cover the expense of shipping items to British Guiana for exhibition. Another collection on display in 1885 was uncovered in the grounds of a sugar plantation, Enmore, in British Guiana. This plantation had been in the hands of the Porter family for over a century. It was Rashleigh Porter, great-grandson of the first Porter (Thomas) who had established the plantation, who reported the discovery of artefacts, including stone tools and "some grotesque clay figures, of a highly artistic kind", as the Editor of Timerhi Everard im Thurn reported. Another rich seam of artefacts was uncovered when agricultural digging on the estate revealed deposits of pottery sherds and human and animal remains. Some of the details about these 'local' (to the Caribbean) exhibitions come from digitised newspapers that have recently been added to the British Library's British Newspaper Archive. In the announcement promoting these newly added resources, the British Library has signalled a commitment to incorporate more colonial papers (and thereby colonial histories). Among the lot available now are searchable papers from Dominica, Jamaica, Barbados and Belize (formerly British Honduras). These now join other digitised searchable resources (see my post "Building Collections Histories") revealing various aspects of the history of the Caribbean in the 19th and 20th centuries. I'm looking forward to exploring these further, and to seeing the collection of available searchable material grow in the coming months! References/Further Reading [Exhibition] Committee, 1885. British Guiana and West Indian Exhibition, 1885. Timehri 4: 268-293 Dominica Dial [Advertisement for Exhibition at Courthouse] [British Newspaper Archive] 24 Oct. Dominica Dial, 1885 British Guiana and West Indian Exhibition. [British Newspaper Archive] 21 Nov. im Thurn, E. 1882. The British Guiana Exhibition of 1882. Timehri 1: 100-117. im Thurn, E. 1884. West Indian Stone Implements; and other Indian Relics (Illustrated). Timehri 3: 103-137. By Amara Thornton

This month I launched the website for a project I've been working on for the past few months: Narrating the Diverse Past. It was a joint University of Reading and British Museum partnership project, and had a number of different parts. One of the parts was a digital interactive exhibition, "Mapping Collections Histories: Connecting Barbados and Britain". This grew somewhat organically from the research I began earlier in the summer (see Colonial Archaeology in the Caribbean), but with a focus on histories of archaeological collections that connected Barbados to Britain (as the title suggests). I've explored some of the storylines in this exhibition via threads on Twitter, but in this post I want to talk a bit more about the illustrations that accompany my text in the exhibition. These are the work of Michelle Keeley-Adamson, whose illustrations from historic excavation photographs I was introduced to during the summer. The Mapping Collections Histories exhibition features three different maps. The base map shows Britain and Barbados "in context" as it were, with a dotted line to highlight the distance (and connection) between them. This is loosely based on an old map of the British Empire. Then there are separate maps of Britain and Barbados. The Barbados map shows the basic outline of the parish boundaries (the equivalent, basically, of counties in the UK), and has 5 illustrations superimposed to highlight five locations relevant to the theme of the exhibition. Each illustration draws inspiration from historic photographs or drawings that we found online. The illustration for Farley Hill, home of Barbadian collector Thomas Graham Briggs, was based on an old postcard; the drawings for Mount Ararat Estate and Conset point were based on illustrations in an article published in 1870 by the British antiquarian Greville Chester, who explored, collected and conducted an excavation during his roughly year long residence in Barbados in the late 1860s. The illustration for Bridgetown is based on historic photographs of the city streets. The illustration for Codrington College is based on photographs from old Barbados guidebooks online. For the Britain map, again we turned to historic images found online and digitised books. One of the most exciting elements of this map for me was seeing Michelle's recreated display interiors for the Colonial and Indian Exhibition 1886, drawing inspiration from sketches in the Illustrated London News and Frank Cundall's Reminiscences of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition. The Blackmore Collection in Salisbury image is based on old photographs and an Illustrated London News drawing of the interior of the museum, which was closed in 1930s. I hope you enjoy the exhibition as much as I enjoyed creating it! By Amara Thornton

For the past few months, I have been investigating the history of archaeology and archaeological collecting in the Caribbean island of Barbados in some detail. This is part of my current research project called "Narrating the Diverse Past" (of which more to come!). As one of the oldest English colonies in the Caribbean, first established in the 1620s, Barbados's long historic connection to the UK pre-dates the Acts of Union which brought England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland together to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (now the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland). These connections are becoming more visible in the heritage landscape in Britain today. Reports on historic properties and monuments connections to the Caribbean have been produced by English Heritage (2007,2013) and, most recently, the National Trust (2020) and the Colonial Countryside project. Work is ongoing in Scotland exposing the links between Scottish heritage sites and houses and slavery. The Legacies of British Slaveownership database is also an important resource for exploring links between Britain and Barbados, as it pulls together records on individuals who received compensation for the freeing of the enslaved people forced to make the Caribbean a profitable enterprise for others. These projects have drawn much attention both to the horrors of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and to the diversity of the beneficiaries of the compensation, the debt for which the UK Treasury only paid off in 2015. But my primary area of focus has been on the period after slavery was abolished, and aspects of the continuation of the connection between Britain and Barbados during the rest of the colonial period (Barbados gained independence in 1966, and just this year the Barbados government announced it would no longer have the Queen as head of state). One of the ways in which this post-slavery connection can be explored is through university records. Beyond Oxford and Cambridge these records can be difficult to source, depending on how universities recorded the student body over time, and how much effort (and resource) has been devoted historically to maintaining and researching these records. However, Oxford and Cambridge are a useful starting point, particularly because both Universities attracted students whose families had long-standing connections to Barbados (some established during the days of slavery and continued through sugar production after emancipation) and because many Oxford and Cambridge graduates were employed in various roles in administration, education, and the military, across the British Empire. Cambridge University has developed an online searchable database for its student records, and these records comprise an illuminating dataset for British-Caribbean connections (see also the Black Cantabs project). Combining biographical details from published student records produced in the early 20th century, with lists of students attending Cambridge's women's colleges (women attending Cambridge could not be full members of the University, or get Cambridge degrees, until 1948), this database is a valuable historical resource. The records it pulls together for Barbados, for example, show that Barbados' Cambridge connections stretch back to the late 17th century. The more than 320 records of students with links to Barbados cover various relationships to the island: students who were born there, whose parents were born there, who worked there, who inherited property there, who married someone from there, who died there – and sometimes a combination of all of these. For my purposes, at least two of these student records are significant in the archaeological collecting history of Barbados (though I suspect there are probably more). Thomas Graham Briggs (1833-1887, B. A. 1856, M. A. 1862) and John Poyer Poyer (1843-1925, B. A. 1866, M. A. 1869) both exhibited artefacts from Barbados in the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition. Both men had family estates in Barbados. At present I know nothing about John Poyer Poyer's collection, beyond the fact that his "Carib relics" were on display in the Barbados room of the Colonial and Indian Exhibition. Historic records and artefacts from Barbados belonging to Thomas Graham Briggs were on display in various parts of the exhibition. A selection of Briggs' artefacts is now in the British Museum, acquired a year or so after his death in London in 1887. According to the Museum's Collections Online, these are not from Barbados but rather a smattering of other Caribbean islands, including Nevis, where Briggs owned three estates in addition to his estates in Barbados. (There will be more from me on Thomas Graham Briggs and his artefacts coming soon.) These two individual stories are just the tip of the iceberg, as the saying goes, in exploring the educational connections between Britain and the Caribbean. I hope that more UK universities can put resources into investigating and publicising their institutional histories and student records to reveal these imperial connections. The University of Edinburgh has begun this work with its Uncover-Ed project; Pamela Roberts has been working at Oxford on the Black Oxford project. The University of Glasgow, similarly, has a website for its historical international student body called International Story. Codrington College in Barbados (Thomas Graham Briggs' alma mater) had a historic tie with the University of Durham from 1875 to 1955, during which students could take degrees from Durham. In the 19th century the UK university sector expanded significantly as universities and university colleges opened in various cities and towns across England. I'd love to know how many Barbadians were able to take up opportunities to study here during that period, and what happened to them... By Amara Thornton

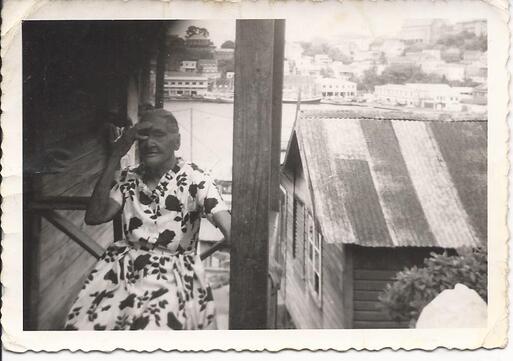

Earlier in the summer I started an investigation of the history of archaeology in the Caribbean during the late 19th century. When writing the post I came across references to Irish artist and author Edith, Lady Blake, wife of the Governor of Jamaica, who was credited with being a local collector and promoter of archaeology on the island in the Institute of Jamaica Journal. In 1890 Edith Blake wrote an article, "The Norbrook Kitchen Midden", published in the Victoria Quarterly, a short-lived periodical associated with the island's similarly short-lived Victoria Institute. Established in 1887 in association with Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee (celebrating 50 years on the throne) the Victoria Institute was, according to the Handbook of Jamaica, devoted to "the intellectual improvement of its members and the promotion and cultivation of a taste for literature, science and art in Jamaica generally." Judging from the tables of contents of the Victoria Institute's Quarterly (some of which have handily been put online here) it served as a general periodical for science, literature and history – the perfect venue for Blake's article. At the time I wrote my initial post, I had not yet been able to access a copy of the original article, but surmised that it comprised a summary of her excavation of the site. I've now seen it, and to my surprise it reveals not only Lady Blake's association with the site, but the role of another woman as well. Blake's "Kitchen Midden" is a summary of discoveries made in fields near the Shortwood Teacher Training College, and Blake's speculations on their significance, rather than an explicit presentation of work that she had directed herself. She reported that children finding shell fragments on a site significantly far away from the shore had collected them and brought the collection to Amy Charlotte Johnson, the Principal of the Training College. Johnson had studied at Oxford, obtaining an "Associate in Arts", and had further obtained teacher training at Cambridge before she took her post in Jamaica in 1885. (Her movement from the UK to Jamaica – and, presumably, back again – is part of a larger history of education in the colonial Caribbean). It appears that Johnson had some familiarity with archaeology – in 1889, four years after her arrival, she published an article titled "The History of Auvergne", in the Victoria Quarterly. It included a summary of the archaeology of the region and its links to Etruria. Johnson was clearly invested in building up the Jamaica's cultural resources; thanks to the digitised archives of the Jamaica Gleaner I found that she also donated a live specimen to the Institute of Jamaica Museum in 1895. She left her post in 1899, and it's not clear at the moment what happened to her thereafter. By the time Edith Blake wrote "Kitchen Midden", she had already established her interest in archaeology. While her husband was Governor of the Bahamas, in the years prior to their arrival in Jamaica, she had explored caves in Rum Cay, a small island south of Nassau. The sketches she made of petroglyphs from this cave, and her short report documenting her trip, were published in the Journal of the Bureau of Ethnology. It's hard to say at this stage how much involvement in the excavation of the Norbrook Kitchen Midden either Edith Blake or Amy Charlotte Johnson had. The Institute of Jamaica Journal records that the Committee of the Institute was responsible for directing the work; but I suspect that both women were involved in some capacity, probably unofficially. There will hopefully be more to come! References/Further Reading Blake, Edith, 1890. The Norbrook Kitchen Midden. Victoria Quarterly 2(4): 26-33. Coburn, Patrick, 2011. The girl in the painting. Independent. 28 June: 12-13. Daily Gleaner, 1889. The Victoria Quarterly Magazine. 5 August: 2. Daily Gleaner, 1891. Institute of Jamaica: The Museum. 13 November: 2. Daily Gleaner, 1899. The Case of Miss Johnson. 21 March: 7. Mallery, Garrick. 1893. Picture Writing of the American Indians: Bahama Islands [Edith Blake's report]. Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnography. Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 137-9. By Amara Thornton I first drafted this post in the summer of 2017, moved to respond to news of a poll indicating that a large majority of people in the UK felt the British Empire was a legacy to be proud of. But I never published it. At the time, it felt too personal and there were discrepancies I couldn't satisfactorily resolve, as you will see. A bit over three years on and the issues that had inspired me to write this post in the first place are still here; the legacy of empire remains a hotly contested topic. But the responses to that legacy and the context of empire are now, I think, moving (if slowly) in the right direction. Lack of basic knowledge about Britain’s Empire is one of the issues that has been identified in the debates. I didn’t go through the UK school system, so I can only refer to what others have said about the absence British imperial history in the primary and secondary school curriculum. But TV programmes such as David Olusoga’s Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016), and Olusoga's book of the same title, have begun to present that history. Several Who Do You Think You Are episodes have exposed various celebrities’ imperial roots.* If you read this blog regularly, you’ll know that as a researcher I spend a fair amount of time finding out how British archaeologists lived and worked in countries that were, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, informally or formally administered by Britain. But for this post, I’m going to look at how the British empire affected one branch of my own family tree. One of my great grandfathers was Joseph N. Maxwell. I’ve never seen a picture of him, but I do know a bit about his life thanks to two eighty-odd year old letters, kept in the family. Blurry photographs of photocopies of them are currently lurking in a folder on my computer. They are petitions written by my great grandmother Rosilia Maxwell in February 1932 in order to plead with the government of Grenada for the continuation of badly needed pension funds. Her husband Joseph had died the previous September, only four months into his retirement, after a total of 32 ½ years of public (government) service. Rosilia was now the sole provider for several children under eleven years of age. These petition letters offer a window onto a bit of Britain’s imperial history. Grenada is a very small predominantly mountainous island in the Caribbean, near the northern coast of Venezuela. By the 1930s, it had been a British colony (ceded by France) for nearly 150 years, and it was the headquarters of government for the Windward Islands - Grenada, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines. The letters are written from the island’s largest town, St George’s.

In order to support her case, Rosilia outlined her husband’s professional career in some detail. He had retired as Senior Warder at Richmond Hill Prison after 22 ½ years in prison service, and he had previously worked in Grenada’s Public Works Department. While he worked at the Prison, the Maxwells had lived on a house nearby which it seems came with the job; one of the major expenses she had was paying for the construction of a new house for herself and her children to live in. I know from experience that it can be very difficult to find documentation of roles beneath the top layer of Departmental officials in printed records (such as Blue Books, Handbooks, or Civil Service lists). Records of British colonial administrations are also patchy - Operation Legacy is reflective of that.** So I have no idea at present in what capacity Joseph worked for the colonial Public Works Department. But before that, Rosilia declared, Joseph had served in HM forces, as a gunner in the St Lucia Garrison Artillery, during which time “…your Excellency’s petitioner’s late husband Joseph N. Maxwell served as a soldier in the Boer War.” To discover more about his Boer War service, some years ago my mother went to the National Archives in Kew. There, in WO97 files (War Office discharge papers) she found a likely candidate. A “Joseph Maxwell”, born in 1870, a British subject in Barbados. This Caribbean island had been a British colony since the 17th century. This Joseph worked as a groom, probably in St George parish where his parents lived, until 1892. In August that year he joined the Royal Artillery’s St Lucia Company as a gunner. He signed his name on the recruitment form clearly and legibly, declaring his intention to serve in the Artillery for the next twelve years of his life. A 5 foot 7 inch man with a dark brown eyes and black hair. Complexion: black. He was 22. Barbados was the headquarters for Britain’s military forces in the Caribbean. The first few years of Joseph’s military service were, shall we say, chequered. His record indicates that about six months after he joined up he was in civil custody, eventually he was tried and imprisoned for a hefty nine months for lashing out at the civil police. He returned to duty in January 1894, only to be put on trial toward the end of 1895 and imprisoned again (with hard labour this time) for nearly three months. No charge was recorded for the second imprisonment. But, this wasn’t enough for him to be kicked out of the Artillery. By February 1896 he was back on duty. Perhaps he decided prison sentences weren’t getting him anywhere. In fact, his service record indicates that before he was finally discharged in 1901 as “medically unfit for further service” he had been granted “GC [good conduct] pay” twice, in October 1899 and October 1901. What could have occasioned this change? Joseph’s first lot of “GC pay” came just four days before war between Britain and the South African Boers was officially declared on 11 October 1899. I have no idea whether Joseph actually went to South Africa, or what he might have been doing there if he did. On the form listing his “Service at Home or Abroad” the column for “countries” only says Barbados. I’m not a military historian, so perhaps there’s more that can be inferred from these records that I’m not aware of. (If you know more do get in touch!) However, troops from the Caribbean were involved in the Boer War, as my great grandmother's letter attests. Interestingly (given my great grandfather's post-war profession) one of the roles these Caribbean soldiers had was guarding prisoners of war. Boer prisoners were held in British run concentration camps in South Africa; but they weren't only held there. POW camps were established in a variety of places including St Helena (where Napoleon had been held earlier in the century), Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India and in the Caribbean at Bermuda (newspapers reported plans to house prisoners in other islands, including Barbados, were later abandoned because the war ended). History works best, I think, and is most effectively communicated when it’s human – by which I mean the messy, confusing, wonderful, depressing stories of everyday life. Those stories cut across every stereotype and assumption about class, race, gender, nationality. People are people no matter where they’re from or what they look like. Now, there’s only so much you can do as a historian with what’s left, but you can have a go at building up a history. So here’s my attempt. Fragments of one man and one woman’s story to illuminate a small bit of Britain’s imperial history. Maybe it’ll resonate with other people. If it does, my job is done. For now. References/Further Reading Benbow, Colin, 1982. Boer Prisoners of War in Bermuda. Bermuda College. Boer, Nienke, 2017. Exploring British India: South African prisoners of war as imperial travel writers, 1899-1902. Journal of Commonwealth Literature: 1-15. Derby Daily Telegraph, 1902. The Boer Prisoners at Barbados. [British Newspaper Archive]. 23 May. Olusoga, David, 2016. Black and British: A Forgotten History. London: Pan Macmillan. Royle, Stephen. St Helena as a Boer prisoner of war camp, 1900-2: information from the Alice Stopford Green papers. Journal of Historical Geography 24 (1): 53-68. Sheffield Evening Telegraph 1902. West Indies and Boer Prisoners. [British Newspaper Archive], 3 July. The National Archives. Service Record: Joseph Maxwell. TNA WO97/5488. * These include (for the Caribbean islands), Moira Stuart (2004, Antigua & Dominica); Colin Jackson (2006, Jamaica); Ainsley Harriott (2008, Jamaica & Barbados); Gwyneth Paltrow (2011, Barbados); John Barnes (2012, Jamaica); Liz Bonnin (2016, Trinidad & Martinique); Noel Clarke (2017, Trinidad, Grenada & Carriacou); Marvin Humes (2018, Jamaica); Naomie Harris (2019, Grenada & Jamaica). ** See Dr Mandy Banton's excellent talk about colonial administrative records here. The Museum of British Colonialism has also been doing excellent work drawing attention to Operation Legacy. By Amara Thornton

In the past month I've finally been able to return to the British Library. I'd had a number of things I'd been wanting to see, including two issues of the Victoria Quarterly, a Jamaica-based literary journal published in the 1890s. Having first learned about the journal in the course of researching last month's post "Colonial Archaeology in the Caribbean", I was hoping to see the issue in which Lady Edith Blake published the article on her excavations on a kitchen midden at Norbrook (Northbrook), near Kingston. But it was not to be – the British Library's two issues were not the ones in which Blake's article appeared. But all was not lost – in flipping through one issue, from July 1892, I came across Mrs Spencer Heaven's story "My Family Mummy". The plot summary is as follows: a party of young cousins are in the ancestral family home over the Christmas holidays. The one 'grown up' around – Aunt Bessie – leaves them to their own devices and only communicates with them through (affectionate) notes. As boredom descends upon the young folks, one of them remarks that the family has a mummy stored away in the attic, a 'relic' of a long-dead ancestor's travels in Egypt. All the others are determined to see the mummy and so they make a pilgrimage to the attic. One of the girls, Maud, sees the mummy for what it is – a human being – and tells the others that respect should be paid to it. Eventually she convinces everyone that the mummy, nicknamed "Miss Pharaoh" should be reburied. After some discussion, during which it is determined that no suitable ground could be found for the reburial, Maud decides that cremation would be best. A day is chosen, the fire built and "Miss Pharaoh" burned. The cousins abandon the fire to the care of servants and go to town, but it transpires that eventually the servants are arrested for murder; the police have found a burning corpse in thier charge. The young folks are both horrified and convinced that "Miss Pharaoh" is seeking revenge. However, the story ends tidily with them rescuing the servants from probable hanging by explaining the situation in court. The story is presented as being an anonymised re-telling of events that actually happened – whether or not that is true I'm not sure! But it's certainly fictionalised, if not fiction. Having literally just listened to an excellent panel on ancient Egyptian human remains ("Your Mummies Their Ancestors") this 19th century story reflects a discussion about how 'mummies' are viewed, displayed and interpreted that is still continuing today. [Originally from Devon, Selina Frances Smyly married De Bonniot Spencer Heaven of "The Rambles" and "Whitfield Hall" Jamaica in 1864. She lived in Jamaica for many years before returning to Britain, where she died in 1911. She was a musician and botanist as well as a writer.] References/Further Reading Colonies and India. 1893 [News]. [British Newspaper Archive]. 4 Feb: 11. Exeter and Plymouth Gazette. 1864. Abbotsham. Wedding Festivities. [British Newspaper Archive]. 11 Nov: 6. Heaven, Mrs Spencer (Selina). 1892. My Family Mummy. Victoria Quarterly 4 (2): 16-26. Stienne, Angela (Ed). Mummy Stories[Blog] Western Daily Press, 1911. Deaths. [British Newspaper Archive]. 26 June: 10 Hartland and West Country Chronicle. 1911. [News] [British Newspaper Archive]. 15 June: 9. By Amara Thornton I've been researching the history of archaeology for over a decade now, concentrating on excavations done in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. That's due entirely to the fact that my PhD research began with the archive of two British archaeologists who worked in Jordan; this and my subsequent research has focused in various ways on the network of British archaeologists they were a part of. The countries this network was active in – Egypt and Sudan, Mandate Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq – were tied to the British Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in one way or another. But there is another part of the British Empire that I've neglected in research terms, and it's a lot closer to 'home'. That part is the Caribbean, and its where half of my own heritage lies. Lately, I've been taking a closer look at the history of archaeology in the Caribbean. Now, I'm not an expert on Caribbean history. Having grown up in the US, it's not something I learned in school (though had I grown up in Britain, I wouldn't have learned about it in school either). That's partly why I'm writing this post. But I'm also intrigued to find out how the history of archaeology and development of (for want of a better term) archaeological 'heritage' infrastructure in the British Caribbean compares with the British-occupied countries I've spent so long researching. Antiquities from the Caribbean were being actively collected and displayed in Britain by the 19th century, including at the Blackmore Museum in Salisbury, and in large-scale exhibitions such as the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in South Kensington. In the Caribbean (as far I understand at the moment) the island with the most formally organised archaeological infrastructure at that time was Jamaica, the largest island in the British Caribbean, and the island with the largest population. English forces captured Jamaica in 1655; it became a colony in 1670. By the mid-19th century it had two 'scientific' societies – the General Agricultural Society of Jamaica and the Society of Arts. These two organisations merged in 1864, and from this foundation the Institute of Jamaica came into being in 1879. The maintenance of a library, reading-room and museum and the provision of programmes of lectures were part of the Institute's charter. Members were elected, and had to pay membership fees. Following the exhibition of antiquities in Jamaica's 1891 International Exhibition, the Institute's work in the mid-1890s began to focus more particularly on archaeology and history. Two consecutive lecture series (costing 5 shillings a ticket, half price for members) given during this time were "Greek Life and Literature" and "The History of Jamaica". William Cowper, later principal of Wolmer Free School, delivered both series. In addition, the Institute's journal began publishing reports on archaeological discoveries made on the island. These chronicle the work of Jamaican residents (some of whom were descendants of slave-holding plantation owning families) in uncovering the remains of the island's ancient inhabitants. Where possible, links have been integrated in what follows to the Legacies of British Slave-ownership Database. In 1894, James Edwin Duerden, a British zoologist, was appointed Curator of the Museum. While the original focus of the collections had been natural history specimens, under his aegis in the summer of 1895 a circular was sent out for collections of Jamaican antiquities to be loaned for exhibition. This circular was inspired in part by discoveries made by Irish artist and naturalist Lady Edith Blake (resident in Jamaica at the time with her husband Henry Arthur Blake, the colonial Governor of Jamaica). She had written up her work formally in an article in the Victoria Quarterly, a journal of the Victoria Institute, a Jamaica-based learned society. She also wrote a general history of Jamaica's ancient inhabitants for Appleton's Popular Science Magazine. At the moment, I can't find a copy of her Victoria Quarterly article online, but the American traveller and author Frederick A. Ober quoted her description of the excavations she directed at Northbrook (Norbrook) in St Andrews parish near Kingston in his 1895 article "Aborigines of the West Indies". Exhibitors in the 1895-6 Institute of Jamaica museum display included Lady Blake and "Miss Moulton Barrett", daughter of Charles John Moulton-Barrett who was poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning's brother (stay tuned for more on "Miss Moulton Barrett" in due course). Duerden followed up on various leads identified in the reports gathered from residents, and his 1897 publication "Aboriginal Indian Remains in Jamaica" (Vol II No 4 of the Institute's Journal) gives a fascinating insight into the community of 'amateur archaeologists' on the island. In fact, it's clear from this that the Institute of Jamaica seems to have been rather a hub for the archaeology of the Caribbean. The exhibition featured artefacts found not only in Jamaica but also in Grenada and Barbados (sent by a Rev. T. W. Bindley of Barbados) and British Guiana (now Guyana), and communications on antiquities were received from Dr C. W. Branch in St Kitts. With the end of the exhibition the artefacts displayed were scattered far beyond Jamaica. In his 1915 book Historic Jamaica, Institute of Jamaica Secretary Frank Cundall noted (in a prescient observation given current repatriation debates): "it is to be regretted that many of the objects shown at the exhibition of native remains held at the Institute of Jamaica in 1895...should have been allowed to leave the island. Such things once lost can rarely be regained." At least some of the objects from Jamaica (like these artefacts attributed to Lady Edith Blake as owner) are now held by the National Museum of the American Indian, part of the Smithsonian Institution in the United States. The two islands that have the greatest familial significance for me are Grenada and Barbados. As far as I know from family history research, the majority of my Caribbean ancestors lived for at least a century in Barbados (a colony from 1627) until they emigrated to Grenada (a colony from 1763) at the turn of the 20th century. My grandparents subsequently moved from Grenada to Trinidad (a colony from 1797, where members of the government started plans to create a museum in the 1880s). Guidebooks from the early 20th century noted that those interested in antiquities in Grenada could take themselves to Mount Rich, on the grounds of a former sugar plantation in St Patrick's parish on the north of the island, where ancient petroglyphs could be seen carved on the surface of the rock. An English minister and resident in nearby St Vincent, Thomas Huckerby, wrote a paper on these petroglyphs in 1921. Antiquities from Grenada were also displayed in the 1905 Colonial and Indian Exhibition, held at the Crystal Palace. In Barbados, meanwhile, by the late 19th century a collection of antiquities, described by a visitor as "a litter of Carib curiosities", could be seen at Farley Hill Mansion in St Peter's parish, the home of Sir (Thomas) Graham Briggs. In St John's parish near Codrington College (the only institution of higher education on the island) could be found more remains of the ancient indigenous population. These were described briefly by British antiquarian Rev. Greville Chester in his 1869 travelogue Transatlantic Sketches. Chester noted the work of one Barbados-based antiquarian and school teacher W. A. Culpeper, whom he met in Barbados during his 1867 trip to the Caribbean. Subsequently Chester donated artefacts from Codrington to the British Museum (though these are not on display). By the early 1890s in his History and Guide to Barbados James H. Stark wrote a plea for an antiquities museum to be established on the island. Eventually, a "cabinet of antiquities" could be seen at Codrington College. Much of the publication of Caribbean archaeology (in this case meaning indigenous native American) during the early 20th century was done by men funded in the United States. Jesse Walter Fewkes and Theodoor de Booy were financed by American banker and collector George Gustav Heye, whose collection was originally shown in his own museum in New York before he set up National Museum of the American Indian in 1916. Their reports were published in American scientific journals, and reprinted in the National Museum's later series. It's critical to note, however, that many of the people coming across the remnants of the lives of the ancient inhabitants of these islands were enslaved or the descendants of enslaved people. They were employed in plowing fields and cutting or digging holes for planting sugar cane. They would also have been the people actually labouring on the excavations conducted. In one of Chester's excavations at a cave on the Mount Ararat Estate in St Michael's parish, Barbados, they were convicts, loaned by the Governor for the purpose. Their names are not mentioned in informal or formal published reports. In one heartbreaking case reported in the Institute Journal, on the grounds of the former sugar plantation Wales Estate (Trelawney, Jamaica) the remains of ancient indigenous habitation were mixed in with the material remains of enslaved people whose then-abandoned home had been built on top. Such moments of discovery were also reported through memories, which were then written into archaeological reports to provide context for collections. Following his trip to Barbados in 1912-13, Jesse Fewkes noted "A negro woman, who lives in the plain near the caves [at Mount Gilboa (now Mount Gay), St Lucy's parish, near the former estate of John Pickering] told the author that shell chisels had been found within her memory on the talus below the caves...." Nearly half a century earlier, West India Regiment Lieutenant Alwin S. Bell wrote in a letter from Falmouth, Jamaica (later read out at a meeting of the British Archaeological Association) that he discovered Black Jamaicans possessed ancient stone tools, which they put in water jars to keep the water cool. He collected some from them, reporting I have since obtained several, in all about thirty (mostly from the old black people, formerly slaves) in the country districts. These have all been found at various periods, but chiefly during the slave time, when the greater portion of the island was under cultivation." One could argue, then, that the enslaved and formerly enslaved people were the original explorers, excavators and collectors in the Caribbean.

References/Further Reading 1922.Thirty-Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington: Government Printing Office. Allsworth-Jones, Philip. 2008. Pre-Columbian Jamaica. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. Atkinson, Lesley-Gail. 2006. The Earliest Inhabitants: The Dynamics of the Jamaican Taino. University of West Indies Press. Blake, Lady Edith. 1890. The Norbrook Kitchen Midden. Victoria Quarterly (October). Blake, Lady Edith. 1897/8. Aborigines of the West Indies. Appleton's Popular Science Monthly 52: 373-487. Chester, Greville J. 1870. The Shell-Implements and Other Antiquities of Barbados. Archaeological Journal27: 43-53. Chester, Greville J. 1869. Transatlantic Sketches in the West Indies, South America, Canada, and the United States.London: Smith, Elder & Co. Cuming, H. Syer. 1868. Proceedings of the British Archaeological Association. Journal of the British Archaeological Association 24 (4): 391-404. Curet, L. Antonio and Maria Galban. 2019. Theodoor de Booy: Caribbean Expeditions and Collections at the National Museum of the American Indian. Journal of Caribbean Archaeology 19. Duerden, James E. 1897. Aboriginal Indian Remains in Jamaica. Journal of the Institute of Jamaica2 (4). Ellwood, C. V. and J. M. V. Harvey, 1990. The Lady Blake Collection: Catalogue of Lady Edith Blake's Collection of Drawings of Jamaican Lepidoptera and Plants.Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History)18 (2): 145-202. Ford, J. C. and Findlay, A. A. C. 1903. The Handbook of Jamaica. London: Stanford. Franks, A. W. 1868. British Museum Guide to the Christy Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities and Ethnology.London: British Museum. Howard, Robert R. 1956. The Archaeology of Jamaica: A Preliminary Survey. American Antiquity 22 (1): 45-59. Huckerby, Thomas. 1921. Petroglyphs of Grenada and a Recently Discovered Petroglyph in St Vincent. Indian Notes and Monographs. Keegan, William F., Hoffman, Corinne L. and Reinel Rodriguez Ramos. (Eds.). 2013. The Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Maderson, Paul. 2014. James Edwin Duerden 1865-1937: Zoological polymath. In Jackson, Patrick N. Wyse and Mary E. Spencer Jones (Eds.) Annals of Bryozoology 4: aspects of the history of research on bryozoans: 231-265. Ober, Frederick. 1895. Aborigines of the West Indies. Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society. Vol 9. Pepper, George H. The Museum of the American Indian. Heye Foundation. The Geographical Review 2 (6): 401-18. Stevens, Edward. 1870. Flint Chips: A Guide to Pre-Historic Archaeology Illustrated by the Collection in the Blackmore Museum, Salisbury. London: Bell and Daldy. By Amara Thornton I've have been occupying myself with (among other things) a digital bundle of old letters – one of my favourite things. These letters are rather more personal than my usual though; they are from my great-grandfather to his sister and were sent during the middle of the First World War, between May 1915 and July 1916. They are almost invariably signed off "Your Bro, Alex", which makes me smile. My great-grandfather Alexander Palmer Kelly was from North Carolina. As a twenty-nine year old recently graduated doctor in early summer 1915 his first job was not on land at all but at sea. He signed on to his first ship Hydaspes (a British & South American Steam Navigation Co. vessel) in June as ship's surgeon, beginning what would be at least a year of near continual travel across the Atlantic and through the Mediterranean. The salary was good, and offered him the chance to pay off various medical school debts. Equally, I think, this was a once in a lifetime opportunity – an adventure with much more than a hint of danger. The sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania, targeted by German submarines en route to Liverpool from New York with the loss of over a thousand passengers, had occurred just over a month before he departed on his first voyage.

I was helped in my quest to follow his footsteps abroad by the extremely handy 1915 Merchant Navy Records project, a searchable database of digitised Merchant Navy crew lists hosted by the National Archives and the National Maritime Museum in London. Using this database I was able to find him on four different ships – Hydaspes, followed by a very brief stint on Sachem, and then two consecutive trips on Turcoman (Dominion Line). On these he sailed through North Atlantic routes, calling at ports in Canada, Ireland and England. He joined the S. S. Parisian in late December 1915. A Leyland Line vessel, Parisian was bound for Alexandria. This would be his first time going so far east, and he was very enthusiastic about it. It would also be his first Christmas outside the United States. Parisian was carrying mules (bound, I assume, for war service) and the trip east it seems was uneventful. By Boxing Day he was in Alexandria harbour, soaking up the sun and the (to him) completely new culture of Egypt. Having gone "from the farm to the sea" (as my grandmother later put it) he thought Egypt was worth travelling through the war zone to get to. He thoroughly enjoyed shore time in Alexandria, abandoning his plan to visit Cairo in favour of staying put. He rang in the New Year with many others at a dinner at the Majestic Hotel (the very hotel where novelist EM Forster had established himself on arriving in Alexandria only a month earlier).* The city was thronging with soldiers and sailors, Egypt being a key staging post for campaigns in the Eastern Mediterranean. While he was in "Alex", disaster struck. S. S. Persia, a commercial passenger ship run by the Peninsular and Oriental (P&O) line, was torpedoed in the waters between Crete and Alexandria. Hundreds of people drowned; the ship sank quickly when the boiler exploded as a result of the hit. What survivors there were floated in lifeboats on the open water for over a day before rescue. They were brought to Alexandria, where my great-grandfather saw them land. They were mainly coatless and hatless he observed (and very probably cold). He writes almost breezily about this tragedy, but reading between the lines I think the danger of his choice of sea over land rather haunted him. The Parisian had followed exactly the same route as the Persia, less than a week earlier, so what happened to its passengers could very well have happened to him. Enemy submarines, he wrote, "don't bother us but wait for the women and children." By the beginning of February 1916 he was back in the US, but not for long. He re-joined the Parisian for another trip to the Mediterranean via Gibraltar, expecting to stop again at Alexandria. Going by my great grandfather's letters, by this point in the war the Parisian was fitted with guns for ports east of Gibraltar (moving from SS to HMS), and was at the beck and call of the Royal Navy. Before heading out he was full of anticipation for the journey, writing "This is a very fine trip and the submarines and sea raiders only add a little excitement to the thing." Planning ahead for his sojourn in Egypt, he anticipated buying "curios" (as many troops stationed in Egypt did) to bring back as presents. But Egypt was not to be on this voyage. Parisian instead headed for Salonika (Thessaloniki) in Greece, another key port in the war's Mediterranean theatre. When he arrived, the Salonika campaign was ongoing. He wrote, "I am in my glory now getting around where something is going on." Unfortunately I have no idea what he got up to at Salonika, but an article on his exploits published in a local newspaper on his return suggests that he spent some time walking around the city. (By the time he was in Salonika, a temporary museum for antiquities found during war trenching had been set up in the White Tower on the harbour, but it wasn't open to the public so it's highly unlikely that he saw it.) A short time back in the US and he was back at sea on board Parisian once more. The few letters I have from this period are very sketchy in detail. It seems clear the ship was on active service in mid-late May through July 1916, and my great-grandfather was wary of the censor. The last letter in my bundle is from July 1916, written en route back to the US. Frustratingly, in his last sentence he mentions going to Cairo and Algiers. He saw the Pyramids at Giza just outside of Cairo, which he observed were "perfectly grand". I don't know whether this was his last trip on the Parisian – I suspect not as he seems to have found a ship with a route he liked. At any rate, sometime after the United States entered the war in 1917 he joined the US Army Medical Corps and began a thirty-year career as an army medical man. It's been fascinating to dive into what remains of his correspondence from his first years as a qualified doctor during wartime. I only wish there were more. Further Reading Shapland, A. (Ed.). 2018. Archaeology Behind the Battle Lines. London: Routledge. *Thanks to my father for flagging up the Majestic's importance! By Amara Thornton

Last year, I worked as Associate Producer on a history app for iPad, Ballista Media’s Timeline Civil War. While researching the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad for the app, I was intrigued to find a guidebook from 1873 on Internet Archive. The 132 page book appears to have been produced specifically for B&O passengers, and was advertised as the “only special Guide to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Circulated on Its Lines” which could be found “on every passenger train” of the railroad. It’s essentially a 19th century (slightly more formal) version of the travel magazines you find in the back pockets of seats on trains and airplanes. Having been brought up in Maryland, the long history of the B&O was nothing new to me. What caught my eye, however, was the fact that the railroad tracks passed close enough to the ancient Adena civilisation’s 69 foot high mound at the appropriately named town of Moundsville, West Virginia to warrant special note in the guidebook. (The mound and its proximity to the railroad are clearly visible in this 1899 map.) In a chapter entitled “Baltimore and Ohio Railroad”, set amid promotion of the B&O’s history, feats of engineering, luxurious facilities and hotels, and copious full-page advertisements, B&O passengers were directed to view the Grave Creek mound, as it is known. Over the course of a lengthy paragraph on the history of ancient mounds in America, and the results of amateur investigations that had been undertaken at them, passengers were told to consider the fate of the “intelligent and artistic” ancient people who had once lived on the land. It didn’t just stop there. Passengers were also asked to turn their thoughts to the fate of the Native American peoples whose lives and culture at that moment were being trampled under the relentless expansion of United States westward migration and settlement. I find it fascinating that in the early 1870s a railroad company’s guidebook instructed post-Civil War passengers to view the Moundsville mound and ruminate on the ancient and modern context of its history while the train cars (rather than the British “carriages”) chugged away along the track. It’s clear that the author of the chapter (and most of the book) took an interest in both the railroad and the ancient past – perhaps said author, “John T. King, M. D.”, was none other than B&O Railroad Vice President John King. Whoever he was, I’d like to think that a lifetime travelling on the B&O railroad inspired his reflections on the mound of Moundsville, as he watched the landscape roll past his window. For my purposes though, King’s B&O guidebook is an interesting bit of public archaeology and tourism history rolled into one. References King, J. T. 1873. Guide to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Baltimore. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed