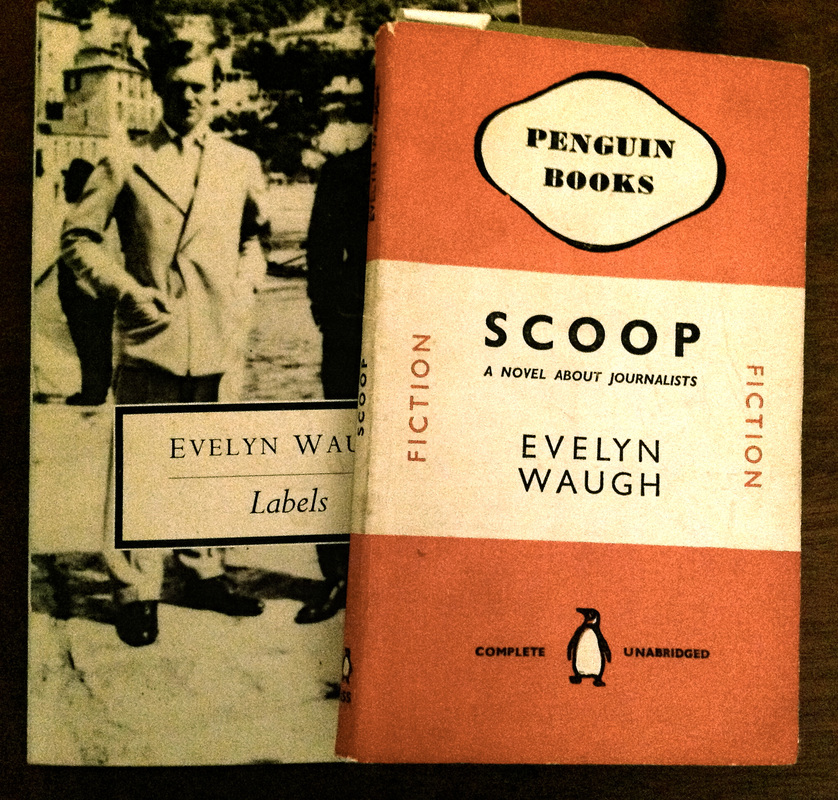

| This post won’t really be about Evelyn Waugh’s novel Scoop, or his travelogue Labels. The title occurred to me after I received Labels as a Christmas gift (at my own request), and I thought I’d use it. I’ve had Scoop on my bookshelf for years, recommended by various people as a light-hearted classic for those interested in folk who went abroad during the 1920s and 30s. But this post is about Waugh. More precisely, Waugh’s observations of his trip to Petra, published in the Palestine Post in January 1936. |

I am, it must be said, rather a sucker for old travel books, as previous posts here make fairly obvious. There is something wonderful about travelling alongside people who are seeing a country – any country – in a past-that-is-their-present.

By the autumn of 1935 Waugh was a veteran traveller. Based primarily in Addis Ababa, he was working for the Daily Mail reporting Benito Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia). But he was fired in December 1935, and he moved on to Jerusalem to celebrate Christmas in the Holy Land. He wrote to a friend of his intention to go to Petra and his difficulties in arranging an affordable trip.

Petra is one of Jordan’s most important tourist attractions. The ancient Nabataean city had been on the tourist roster from the mid-19th century. But by the 1930s, the governments of Palestine and Transjordan (under British Mandates) were promoting archaeological sites as must-see destinations for tourists who could bask in the increased security and safe passage that Mandate infrastructure made possible.

Waugh got to Petra, but not without some difficulty and expense (about £17). Still signing himself correspondent for the Daily Mail, in his lengthy letter to the Editor Waugh’s main bone of contention was that the prohibitive pricing of travel and access to Petra would deter the many tourists on a budget (presumably like him) who came to Jerusalem and wanted to travel in the region.

For Waugh, the fact that the ancient city of Petra is accessed through a passage of outstanding natural beauty without the encumbrances of visible security and management was a benefit. Except that a fee of £1 was levied on tourists for what he considered invisible infrastructure and services, while officials were let in for free even when they were off duty.

I’ve examined the history of heritage tourism in British Mandate Transjordan through the archive of George Horsfield, the British Chief Inspector of Antiquities. Horsfield was responsible for managing said infrastructure of inspectors and sites across the country, so Waugh’s observations on Petra are particularly interesting in relation to Horsfield’s experience. The Department of Antiquities had one of the smallest budgets in Transjordan’s overall expenditure and Horsfield was constantly under financial pressure. I’m not surprised that the prices were so high.

I travelled to Petra as a PhD student six years ago. In 1929 George Horsfield and a small team including Agnes Conway (later Agnes Conway Horsfield) conducted the first scientific excavations at Petra, so I was on the lookout for references to the Horsfields at the site. Sadly I was disappointed – just a brief mention of the first excavation in the Museum with no names attached.

But it’s the people that make a real difference. In 1936, Waugh felt the requirement of a local guide to see the site an expense he could have done without, despite his awareness that the local people depended on tourists for additional income. In contrast, for me the guides and stall-holders of Petra added immeasurably to my experience in 2008. I wrote in my notebook that they “breathe life into what could be considered a remarkably well preserved but unmistakeably dead city”.

Waugh’s letter comes across as fairly petulant. But through his experienced eyes instead of the romantic frozen in time "rose-red" Petra of literature we see Petra-in-practice – a working tourist attraction within a local community who in their own way contributed to the continuity of the site. When Waugh visited Petra it was home to a living community. That community has now been moved following Petra's listing as a UNESCO World Heritage site in the 1980s.

Waugh makes another important point, one which remains relevant today. Here we have the chronicler of Britain’s 'Bright Young People', observer of the amusements of the elite, regretting that the delights of Petra should be affordable only for the traveller with money. The heritage sector still struggles with the balance between preservation, access and economic development within a local context. Waugh's letter, the notes of a journalist and novelist (an 'everyman' if you like), highlights all three issues and exposes the vulnerable underbelly of one of the world's great tourist attractions.

References/Further Reading

Amory, M. (Ed.). 1980. The Letters of Evelyn Waugh. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Horsfield, G. and Conway, A. 1930. Historical and Topographical Notes on Edom: with an account of the first excavations at Petra. The Geographical Journal 76 (5): 369-390.

Stannard, M. 1986. Evelyn Waugh: The Early Years 1903-1939. London: J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd.

Thornton, A. 2012. Tents, Tours and Treks: Archaeologists, Antiquities Services and Tourism in British Mandate Palestine and Transjordan. Public Archaeology, 11 (4): 195-216.

Waugh, E. 1985 [1930]. Labels. A Mediterranean Journal. London: Penguin Books.

Waugh, E. 1936. Prohibitive Petra (To the Editor of 'The Palestine Post'). Palestine Post, 10 January, p. 15. Historical Jewish Press [Online].

RSS Feed

RSS Feed