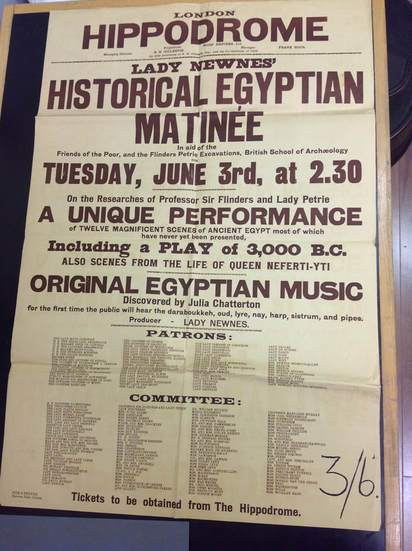

Tuesday 3 June 1930, 2.30 p. m. London’s Hippodrome Theatre. Lady Newnes (aka Emmeline de Rutzen) hosts a “Historical Egyptian Matinee” to raise funds for the British School of Egyptian archaeology's excavations in Palestine and the Friends of the Poor. Mrs Julia Chatterton, a well-known folk song collector, composes all the music for the occasion, to be played on Egyptian instruments. The audience enters to the strains of Verdi’s Aida – first presented in 1871 at the Khedival Opera House in Cairo.

Once everyone is seated, a gong tolls. The familiarity of Verdi gives way to something entirely different, and much more authentic. Julia Chatterton wants the music to take the audience away from themselves, away from London, away from the 20th century. They are to learn and appreciate, the programme notes tell them, “the Oriental mode of musical expressions.”

Julia Cook-Watson Chatterton was no dilettante. She was a member of the Society of Women Musicians before World War 1, she had moved to Egypt at some point before 1914 to edit the illustrated newspaper The Sphinx, and spent ten years living in Egypt with her husband, architect Frederick Chatterton, who was employed in the Egyptian Public Works Department. While there, she began researching Egyptian songs and instruments alongside making her name and garnering official recognition for her work entertaining the troops based in Cairo via the “Cards Concert Party” during the war. Her wartime medals were sold at Bonhams in 2013.

When she eventually returned to England in the 1920s, she began composing pieces with Egyptian themes, using instruments she had collected in Egypt, and presenting them in London. The 1930 issue of Egypt and the Sudan features Chatterton’s article on “The Music of Egypt” in which she attempts to educate English tourists about the history and musicality of Egyptian songs and instruments.

I first came across references to Julia Chatterton’s work on the Hippodrome event some years ago; it’s been on my list of topics to blog about ever since. In preparing for a talk at the Museo Egizio in Turin, I’ve revisited my initial research. Thanks to Petrie Museum curator Anna Garnett and former curator Alice Stevenson, I’ve now been able to see some of the fantastic ephemera created for this event in the Museum's archive.

In the programme, a full picture of the musical programme for the afternoon emerges. Fourteen individual musical interludes, with additional “incidents” occurred during the event. Italian-born London-based composer Francesco Ticciati conducted the orchestra. Noted music historian, archaeologist and British Museum curator Kathleen Schlesinger loaned instruments from her personal collection. Vocalists included one soprano, three mezzo sopranos, two tenors and four baritones (one of whom was Petrie student Gerald Lankester Harding). Among the instrumentalists were a lute player, a tamboura player, a harpist and a pianist. Mamoun Abd el Salam was responsible for playing the nay, the argul and the rebab. Julia Chatterton herself was also one of the musicians playing the darraboukeh, an instrument with which she was particularly skilled, and the kithara.

Complementing the music was a series of fourteen tableaux showing ancient Egyptian history between 8000 and 30 B. C. The performance had 81 cast-members, and “one white pigeon” (representing a dove). It began with a scene of earliest Egypt, accompanied by “Rhythmic Hand Clapping”, showing the Badarian civilisation, the remains of which had recently been excavated by Petrie students Guy Brunton and Winifred Newberry Brunton (also a noted artist). The story of King Khufu and "The Pyramid Age” of the 4th Dynasty was commemorated in Terence Grey’s short play The Building of the Pyramid.

Princess "Sat-hat-hor-ant" (Sithathoriunet), whose elaborate jewellery had been the highlight of Petrie’s 1913-14 season at Lahun, was also featured in the tableaux. The jewellery worn during the performance was recreated from published plates by Lady Leeds (Eltheleen Winnaretta Singer), who took the part of Nefert in the Pyramid Age Tableaux, using cardboard, beads, wax and macaroni. The action wound up in Roman Egypt, with appearances from Marc Antony, Julius Caesar and Cleopatra (played by Lady Newnes herself).

The matinee attracted an audience of 1400 people, among them Princess Beatrice, Queen Victoria’s youngest daughter. Lotus-badge wearing volunteers handed out further information on the British School of Egyptian archaeology’s research, schemes and publications to interested audience members - it was a fundraising venture, after all.

It seems to have been quite the Society event, and there are so many elements to explore in this one action packed aural and visual extravaganza it’s impossible to cover in one blog post, or in one lecture. Needless to say I’ll be returning to this topic in due course, and perhaps someone with a connection to the event will have even more information! (Pretty please?)

*Special thanks to Heba Abd el Gawad for finding suitable links for the Egyptian instruments featured in this piece.

References/Further Reading

Drower, M. 1995. Flinders Petrie: A Life in Archaeology. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Chatterton, J. 1930. The Music of Egypt. Egypt and the Sudan. London: The Tourist Development Association of Egypt, Cairo Station.

Chatterton, J. 1930. The Intimate Significance of Folk-Song. The Sackbut 11 (1): 11-13.

Petrie, H. 1930. Notes and News. Ancient Egypt (Part II, June): 63-64.

The Sketch. 1930. Nefert – and her Egyptian Matinee Jewels of Macaroni. 4 June. p 461.

Times. 1936. Mrs Julia Chatterton. 3 January, p. 17.

Copies of the event poster, programme, and preliminary notice are held in the Petrie Museum archives.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed