Right at the end of the September my latest Beyond Notability blog post was published. 'Modelling Excavations with Wikibase' explores how we have created a model for representing excavations on our Wikibase site, enabling us (where we have the data) to show that excavations are a community. Examples include excavations at Colchester, Essex in the 1930s, and Saqqara, Egypt in the 1900s, drawing on information archaeological reports and popular periodicals.

|

By Amara Thornton

Right at the end of the September my latest Beyond Notability blog post was published. 'Modelling Excavations with Wikibase' explores how we have created a model for representing excavations on our Wikibase site, enabling us (where we have the data) to show that excavations are a community. Examples include excavations at Colchester, Essex in the 1930s, and Saqqara, Egypt in the 1900s, drawing on information archaeological reports and popular periodicals. By Amara Thornton

I seem to have a very informal research strand developing this year uncovering archaeologists suffrage activities – see my post on Jessie Mothersole at the 1911 Christmas Bazaar, and my short piece for the Imperial War Museum's WomensWork100 project on Agnes Conway's interests in suffrage. The British Newspaper Archive has come up trumps again. This time, it's Margaret Murray. Just weeks before war would be declared, suffrage newspaper The Vote noted that Margaret Murray would be one of a number of women participating in a "Costume Dinner and Pageant" to be held in the Hotel Cecil on 29 June 1914. The event was co-organised by the Women Writers' Suffrage League and the Actresses' Franchise League. Now, unless Murray had a stage career that I'm unaware of (unlikely), it seems highly probable that she was affiliated with the Women Writers' Suffrage League. By this point, she had published several archaeological articles and books, including her popular volume of (translated) Ancient Egyptian Legends in the intriguing "Wisdom of the East" series. That April, Ella Hapworth Dixon's article "The Woman's Progress" in the Ladies Supplement to the Illustrated London News had named Murray as "An Antiquary of Note", partly on the strength of her published work. For the dinner, women (and some men) of the day who supported women's suffrage campaigns were asked to don fancy dress to represent famous celebrities from history, stationed at various tables throughout the event space. Each figure was introduced by Cicely Hamilton, founder of the Women Writers' Suffrage League. These historical celebrities weren't just British, though British historical celebrities far outnumbered those of other nations and regions. Egypt, "Asia" (including China, Japan and the Middle East), France, Italy, Finland, the United States were all represented. Murray was the person in charge of the Ancient Egypt table. A review of the event published days afterwards in Vote noted that "Queen Ta-usert" (Twosret), who ruled Egypt in the 12th century BC (and whose jewellery had been discovered in 1908) made an appearance. Whether Murray was actually in costume as Ta-usert/Twosret is unfortunately not stated. But I'd like to think so. In reviewing the event the "Special Costume Diner" of Votes for Women described the memorable fancy dress dinner, which attracted hundreds of attendees, as a "sensation" of mingling with "people who mattered in bygone days impersonated by people who matter today." Of which Margaret Murray was one. References/Further Reading Dixon, E. 1914. "The Woman's Progress". Ladies Supplement to the Illustrated London News[British Newspaper Archive] 18 April. Park, S. 1997. The First Professional: The Women Writers' Suffrage League. Modern Language Quarterly 57 (2): 185-200. Sheppard, K. 2012. The Life of Margaret Alice Murray: A Woman's Work in Archaeology. Plymouth: Lexington Books. Thornton, A. 2018. Archaeologists in Print: Publishing for the People. London: UCL Press. The Vote. 1914. "Costume Dinner and Pageant" [British Newspaper Archive] 12 June: 121. The Vote. 1914. "Women of All the Ages" [British Newspaper Archive] 3 July: 181-2. Votes for Women. 1914. "A Pageant of Famous Men and Women" [British Newspaper Archive] 3 July: 618. By Amara Thornton

The British Newspaper Archive (BNA) regularly releases new titles available (for paying subscribers) to search. I use digitised newspapers regularly in my research, so when in February the BNA announced a raft of new suffragette papers had been added to the collection I was intrigued to see whether these might shed light on the activities of some of the women I've been researching. My curiosity was rewarded recently when I discovered evidence that archaeological-artist (and later author) Jessie Mothersole, about whom I have previously written, participated in the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) "Christmas Fair and Fete" in 1911. I knew Jessie was active in the suffrage movement – in his 1914 memoir her art-tutor Henry Holiday included a suffrage-infused poem she wrote with his illustration on suffrage originally published in Labour Leader, and a copy of her portrait of suffragette Myra Sadd Brown is in the Women's Library at LSE. However, notices in WSPU newspaper Votes for Women, issues of which are now digitised and searchable on the BNA database, reveal that Jessie Mothersole was one of a number of artists involved in creating artwork for the Fair which took place over six days in early December 1911 at Portman Rooms on Baker Street. Various branches of the WSPU were responsible for organising tables and activities at the Fair, representing London neighbourhoods and other cities and regions, including Leeds, Birmingham, Hertfordshire, Nottingham and Kent. Profits were to go towards the WSPU. It seems that Jessie created the signage for the Hampstead WSPU branch's stand (selling chintz and ceramics), which was organised by branch Secretary Lilian Martha Hicks of Finchley Road. Jessie was thanked by name for her efforts alongside other fellow artists in a letter from Sylvia Pankhurst to the Editor of Votes for Women published in the paper on the penultimate day of the Fair. The Women's Library has a series of postcards showing scenes of the 1911 Fair; they are accessible in the Jill Craigie Collection (Ref 7JCC/O/01) at the LSE Library. Thanks very much to Debbie Challis for bringing these to my attention! Debbie has also written about documents relating to archaeologist Hilda Urlin Petrie's suffrage activities; you can read Part 1 and Part 2 of her Hilda history on the Institute of Archaeology History of Archaeology Network website. In related news Fern Riddell's biography of suffragette Kitty Marion, Death in Ten Minutes, has been published this month by Hodder & Stoughton, and the LSE Library's exhibition "At Last! Votes for Women" will be open from next week (23 April) until the end of August. Suffrage historian Elizabeth Crawford has just published Art and Suffrage, a compendium of biographies of artists working for the suffrage movement. Jessie Mothersole isn't included in it, but I'm sure some of the other artists who took part in the Fair are. Her presence at the WSPU Christmas Fair suggests that she supported a more militant approach to suffrage than other women working in archaeology (like Agnes Conway, for example). Just how far that support went, however, remains a mystery. For now. References/Further Reading Crawford, E. 2018. Art and Suffrage: a biographical dictionary of suffrage artists. London: Francis Boutle. Crawford, E. 1999. The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide. London: Routledge. Christmas Fair and Fete. Votes for Women. 18 August 1911: 749. Holiday, H. 1914. Reminiscences of My Life. London: William Heinemann. Pankhurst, E. S. Letter to the Editor. Votes for Women. 8 Dec 1911: 163. By Amara Thornton

The Royal Academy will be turning 250 this year. Two and a half centuries since it was founded to give a home to Britain’s artistic elite. It’ll be interesting to see how the 250th celebrations are received, and what people make of greater exposure of the RA’s history in the forthcoming exhibition (“The Great Spectacle”) and research project in conjunction with the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Personally, I’m pretty excited about the prospect of the RA's historic Summer Exhibition catalogues being made available online (about which more below). 2018 also happens to be the 100th anniversary of the Representation of the People Act, giving a portion of women the right to vote. This centenary celebration is drawing attention to women in history in a number of ways, I’m happy to say. But the Royal Academy has a pretty dire record of admitting women to the lofty heights of Academician status. Beyond 18th century artists Mary Moser and Angelica Kauffmann, who were part of the foundation of the RA, no women were admitted as Royal Academicians until Annie Swynnerton in 1922 (admitted as a Associate RA) followed by Laura Knight in 1936 (admitted as an RA outright). So the result is (by my count, excluding Moser & Kauffmann) only 55 women have been admitted as Royal Academicians between 1768 and now. The Summer Exhibitions, thankfully, tell a different story. That’s why it’s so important that those catalogues are digitised and made available this year. The Exhibition catalogues yield valuable information about the activities of women artists over the course of the RA’s history. And among those women represented in the RA’s Summer Exhibition catalogues are three artists – Jessie Mothersole, Freda Hansard, Florence “Kate” Kingsford – who also worked as tomb-painting copyists for Flinders Petrie in Egypt. In 1906, Algernon Graves published an 8 volume history of contributors to the Royal Academy. This included artists who had had work hung in the RA’s Summer Exhibitions, and it is a fantastic resource for exploring the history of women artists in Britain. So, how are my three archaeological artists reflected in Graves’s history? Well, all three had work accepted in multiple Summer Exhibitions. In 1899, Freda Hansard, listed as a painter, had two works exhibited: “Medusa Turning a Shepherd into Stone” and “Isola dei Pescatori in Lago Maggiore”. Kate Kingsford, also listed as a painter, had “Greek girls playing at ball” accepted and displayed. The following year, Hansard’s “Priscilla”, an oil painting, and Kingsford’s water colour “Harmony” and black & white work “1844” were all exhibited. In 1901, Hansard’s “Rival Charms” was exhibited, as well as Jessie Mothersole’s “Lilian”. Mothersole was listed as a miniature painter in Graves’s history, so this may well have been a miniature portrait. Unfortunately, I have no idea what most of these works looked like, barring a small black & white reproduction of Hansard’s “Priscilla” published in Hearth & Home in May 1900. I don’t know if they are still extant – though you can see two of Freda Hansard’s other paintings online at art.org.uk. One of Jessie Mothersole’s watercolours, displayed at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1911, is also available to see digitally – she included a reproduction of her watercolour “The Oldest Inhabitant – Scilly” in her 1910 book The Isles of Scilly: Their Story, Their Folk and Their Flowers, which you can read and download on Internet Archive. Follow-up volumes to Graves’s History were published in the 1970s, pushing the history of exhibitors to the Royal Academy up to 1970. These illuminate even further the lives of these women as working artists. Freda Hansard (listed as Freda Firth, her married name), exhibited a rather intriguing piece called “Men may come, and men may go, but I go on for ever” in the 1908 Summer Exhibition. I can’t imagine what it looked like, but I hope it’s still around, somewhere. In addition to her contribution to the 1911 exhibition, Jessie Mothersole submitted one painting in 1913, and two in 1914. Two of these paintings showcased Mothersole’s experiences in Egypt – showing Deir-el-Bahari, the site of ancient Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut’s temple, and Abu Simbel. There is a lot of art and associated archive material to explore on the Royal Academy’s new Collections interface. It’s there that I discovered, for example, that Florence Kate Kingsford (Cockerell) exhibited her illuminated manuscripts, including “Hymn to Aten, the Sun Disk” (now held at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge), in the 1916 Arts & Crafts Society Exhibition. And that Winifred Newberry Brunton, another archaeological artist, had her miniature “The Nile” included in the 1915 War Relief Committee Exhibition, held at the Royal Academy. So let’s hope, that with the digitsation of the RA’s Summer Exhibition Catalogues, we start to learn a lot more about the women whose work was featured there, year after year – so that, as I have argued elsewhere, “the digital makes visible the invisible”. Including the work of Misses Mothersole, Hansard, and Kingsford, artists. References/Further Reading Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society. 1916. Catalogue of the Eleventh Exhibition, 1916. (catalogue online via RA Collections beta site) Graves, A. 1905. Preface. The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of contributors and their work.Vol 1 of 8. London: Henry Graves & Co/G. Bell & Sons. Royal Academy. 1900. Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts MDCCCC. One Hundred and Thirty- Second. [Catalogue] Royal Academy. 1911. Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts MDCCCCXI. One Hundred and Forty- Third. [Catalogue] Royal Academy. 1915. War Relief Exhibition in aid of the Red Cross and St John Ambulancew Society and the Artist’s General Benevolent Institution. London: Royal Academy (catalogue online via RA Collections beta site) Royal Academy. 1973-. Royal Academy exhibitors 1905-1970: a dictionary of artists and their work in the summer exhibitions of the Royal Academy of Arts. EP Publishing. By Amara Thornton This month Trowelblazers and Leonora Saunders launched the Raising Horizons exhibition. It features 14 new portraits of historical "Trowelblazers" - women active in archaeology, geology and paleontology. As I mentioned in a previous post, I was asked to portray the Egyptologist Margaret Murray for the exhibition, a great honour. It's been a fantastic project to be involved in - in no small part because I got to dress up for my photograph (though I must admit publicly to a smidgen of costume envy - who wouldn't want a bit of Charlotte Murchison's early 19th century sheen?)

There are several known portraits of Margaret Murray. One, by her student Winifred Brunton - an artist - now hangs on the 6th floor of the UCL Institute of Archaeology. Then there's Murray's Manchester Museum mummy unwrapping-in-action photograph (on which the portrait of Murray in the Raising Horizons exhibition is based). And another six photographic portraits of Murray taken in the 1920s and 30s by studios Lafayette Ltd and Bassano Ltd, now held in the National Portrait Gallery. UCL has some too, including this photograph of her, aged 100, receiving the compliments of the College on her birthday (plus, check out her amazing student/staff record card!)

Just seeing someone's face tells you something almost indescribable. I can see someone's handwriting for years, read their thoughts in letters and diaries, and have a vague picture of them in my head, but there's always something missing without a image of them. Somehow they seem a bit less real. That's what I enjoyed the most about seeing all the Trowelblazers portraits hanging in the Geological Society. It brought home again the fact that these women were alive, human beings, not just names on a page. Raising Horizons is open till the end of the month at the Geological Society and then moving on to other venues - do check it out if you can! For more information, visit the project website: raisinghorizons.co.uk. *My favourite Margaret Murray find remains, unsurprisingly, her curry recipe - more on that here. By Amara Thornton

There are many women artists in the history of archaeology, some of whom I've written about on this blog - Annie Quibell, Lena George, Jessie Mothersole, Freda Hansard, Mary Chubb. In December (2015) I participated in a fascinating workshop, "Overlooked Women Artists and Designers 1851-1918" organised by the Tate's British Art Network. Speakers came together to present on various women artists, their work, networks, spaces and evidence of practice (such as Sally Woodstock's work on the women artists holding accounts at artists' colourman Charles Roberson & Co through the company's account book archive). My paper featured my continuing research on Jessie Mothersole. We were subsequently invited to contribute short pieces based on our papers to a "Conversation" forum on the Paul Mellon Centre's new digital journal British Art Studies. The full (and ongoing) Conversation "Still Invisible?" begins with Patricia de Montfort and Robyne Erica Calvert's "Provocation". Pieces are still being published in subsequent waves. So, Jessie Mothersole is now featured amongst her fellow artist contemporaries once more. I'm sure she'd be pleased. By Amara Thornton

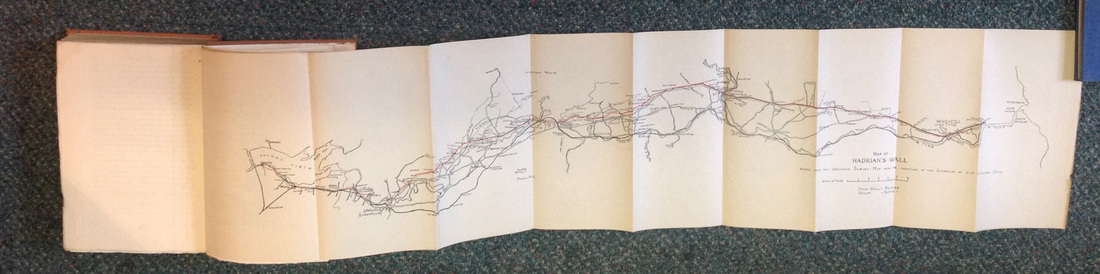

As part of the research I have been doing on women artists in archaeology, this month I wrote a guest post on the Slade Archive Project blog "The Slade Session and Beyond". I introduce UCL's Session Fees book archive as a tool for examining women in archaeology, and I discuss the career of Winifred 'Freda' Hansard, a Royal Academy Schools & Slade School trained artist who (at the turn of the 20th century) began working as an archaeological artist on Flinders Petrie's Egyptian excavations. You can read the post here. By Amara Thornton To Mother That’s the inscription on the inside front cover of my new-old copy of Jessie Mothersole’s Hadrian’s Wall. It’s a first edition, and when I opened the volume I found a lovely surprise inside. By the time “Mother” received Hadrian’s Wall the exhibition had closed. It appears that she and any subsequent readers of this particular book were disinclined to mess about with the pages, so luckily for me the invitation remains loosely attached to the binding. Essex-born artist Jessie Mothersole (1874-1958) trained at University College London’s Slade School in the mid 1890s. In 1899 she began working with the artist Henry Holiday (mentioned in a previous post) as one of several “sister-artists”, as he dubbed them. Her working relationship with Holiday lasted until the end of his life. Her interests in art, archaeology and writing seem to have coalesced during the first decade of the 20th century. She began illustrating books, starting with Charles Stuttaford’s 1903 translation of the story of Cupid and Psyche. In early 1904 she was copying tomb paintings at the ancient cemetery of Saqqara in Egypt alongside Margaret Murray and Royal Academy Schools-trained artist Winifred Hansard. Their work was subsequently displayed in Petrie’s July exhibition of antiquities at UCL. Another trip to Egypt, this time with Henry Holiday, followed three years later. Afterwards Holiday and Mothersole held a joint "Exhibition of Sketches in Egypt and other Works" at Walker’s Art Gallery to showcase the results of their Egyptian tour. Jessie’s first solo-publication was The Isles of Scilly, their story, their folk and their flowers (Religious Tract Society, 1910), which included twenty-four of her own colour illustrations. Isles of Scilly went into at least three editions; clearly her blend of artistic and literary skill was a successful combination. Her next book was Hadrian's Wall. In its Preface, she reveals that the trip along the Wall, the subject of the book, had originally been planned for 1914. But the War, she wrote, “…blott[ed] out all thought of work of this kind.” Eventually in 1920 she embarked for the North to walk the Wall, taking as one of her guides an early 19th century account of a similar trip made by 78-year old antiquarian William Hutton. Her tour took place several years before the Wall was listed as a scheduled (preserved) monument by the forerunner of Historic England, H. M. Office of Works. In the fourth (revised) edition of her book (1929), Jessie called the scheduling "...the greatest epoch in the history of the Wall..."

At the moment I don’t know if Jessie Mothersole had exhibitions to complement each of her subsequent books - another four in total, three of them on British archaeology. I’d love to know if her sales rose as a result of the visibility of her artistic work. What I do know is that at her death her contribution to the interpretation of British archaeology was celebrated, despite the fact that her last book had been published decades earlier. But even more importantly she was one of many artist-archaeologists actively exhibiting in the early 20th century, both male and female. Her contemporary Winifred Brunton (1880-1959) also displayed her works depicting ancient Egyptian people and objects in the Arlington Gallery on Old Bond Street in the 1920s and 1930s.

Take a walk along New Bond Street today and you’d be hard pressed to find representations of archaeology featured in the shops. But the relationship between art and archaeology is still an important one. In the past few years, several exhibitions have explored this nexus, taking inspiration from the archaeological process as well as the ancient artefacts recovered. One of my favourites was 'Nu' Shabtis: Liberation at the Petrie Museum, in which artist and conservator Zahed Taj-Eddin recreated the process of shabti making to bring these ancient Egyptian ceramic guardians into a modern context. References/Further Reading Holiday, H. 1914. Reminiscences of My Life. London: William Heinemann. Mothersole, J. 1922. Hadrian’s Wall. London: John Lane The Bodley Head. Sykes, C. S. 2011. Hockney: the Biography Vol 1. London: Century. The Times. 1958. Miss Jessie Mothersole. Exploring Ancient Britain. April 24, p. 15. *In the 1960s the art dealer John Kasmin built an influential white-cube gallery space on the site. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed